But the method of their engagement with the Spectacle might have turned off Situationism’s founder Guy Debord. As post-punk pioneers with a heavy situationist bent, Morton and Jankel took being on the cutting edge of pop culture seriously. While the creative duo had nothing to do with the Coke campaign, their creation was now leaving an imprint on the consumer landscap e. The subversive paradox created when Max Headroom turned pitchman for corporate cola is just one of many in the career of Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel. In 1986, Coca-Cola launched its “Catch the Wave” campaign: the new face of Coke belonged to Max Headroom. Only this image wasn’t computer generated at all, and it was born from a distinctly anti-corporate sensibility. At the time, a certain computer generated media personality created solely to showcase music videos was becoming quite popular. While previous promotional campaigns focused on virtuous Americana, marketing mavens now needed something more radical and irreverent. Now it was just a matter of selling it back to the young audience who dominated ‘80s consumer culture. Whatever the motive, the original Coke was here to stay-even if it never really left. This led to a boost in sales, with industry insiders speculating that the “great new taste” was nothing more than a marketing scam used to generate renewed product interest. Within three months, the product was pulled due to overwhelming backlash from the public, the original formula reinstated as Coca-Cola Classic.

#Max headroom coke commercial series#

With Coca-Cola’s sugary supremacy challenged in a series of blind taste tests, combined with Pepsi’s subliminal marketing of American patriotism through its red, white, and blue branding, New Coke was introduced in early 1985-a new formula engineered to replace the original company recipe. What began as a pissing contest between beverage barons PepsiCo and the Coca-Cola Company in 1902 eventually became a cultural phenomenon in the mid-1980s. The Max Headroom hackers, who were likely just trying to have a bit of fun, predicted a global movement.Like it or not, we’re all casualties of the cola wars. Informed by the original signal intrusion on that fateful November evening, hacking has moved from the realm of merry pranksters to serious protest, and even government-sponsored terrorism, over the past 30-odd years. Though the true identity of the hackers, and their motivations, are lost in time, the legacy of the Max Headroom Incident endures.

#Max headroom coke commercial tv#

“I got so upset that I wanted to bust the TV set,” one man told a reporter for WGN, one of the affected TV stations. The audiences subjected to the Max Headroom intrusion were deeply perturbed by what they saw. Everest before coming back down.”īut this was 1987–a few years before the advent of the World Wide Web, and long before the concepts of trolling and hacking became known. It’s the equivalent of having your picture taken on the summit of Mt. “It only lasted as long as it needed to get the point across: that point being that the airwaves were woefully unprotected, and easily exploitable. When asked about the motivations for the hack, bpoag likened it to a kind of public service announcement. The ramblings heard in the intrusion, including threats to Chuck Swirsky (a popular Chicago-area sportscaster), and a hummed version of the “Clutch Cargo” theme song, seemed to reflect J’s interests at the time.

The older brother, “J,” had “moderate to severe autism,” says bpoag, but was a capable phreaker. He writes, “All that had to be done, apparently, was to provide a signal to the dish that was of a greater power than the legitimate one.” Later, they told him to tune into channel 11 on the evening of November 22nd.Īccording to bpoag, the actual “hack” was simple enough to pull off, and didn’t require any advanced or technical equipment beyond what an avid phreaker would already have had in his arsenal. In 1987, the week before the infamous hack, the brothers warned bpoag, who was 13 at the time, that they were planning to do something “big” over the weekend.

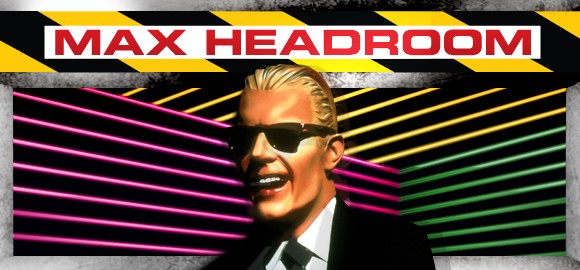

The de-facto leaders of the group were two brothers in their early 30s, called “J” and “K” (bpoag also asked to protect their identities). Here he is as a spokesman for New Coke.īpoag (who asked Atlas Obscura to withhold his real name) was peripherally involved with a group of phreakers operating in LaGrange, a suburb of Chicago. Max Headroom was ubiquitous in the late 1980s.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)